Why does this conversation feel impossible?

You know your mother struggles with the house. The yard is overgrown because she can't manage it anymore. She's stopped cooking because it's too much work for one person. She's lonely since your father died, spending most days alone watching television. Moving to senior living would solve all of these problems. She'd have maintenance handled, meals provided, and people around her daily.

But when you try to bring it up, the words catch in your throat. You know she'll be defensive. You worry she'll think you're trying to get rid of her. You don't want to hurt her feelings or make her think you don't care. So you say nothing, and another month passes with her struggling alone in a house that's become too much.

Tens of thousands of adult children face this same paralysis. You see the problem clearly. You have a solution. But starting the conversation feels like crossing a minefield where any wrong word could damage your relationship permanently.

This article provides the map through that minefield. Real conversation starters that work. Specific phrases to use and avoid. Strategies for addressing the objections your parent will raise. And most importantly, a framework that preserves your relationship while addressing a problem that won't solve itself.

Family Decision Note: Deciding about senior living involves medical, legal, and emotional considerations unique to your family. While we share conversation strategies and what families find helpful, consider involving healthcare providers and holding family meetings to discuss options together.

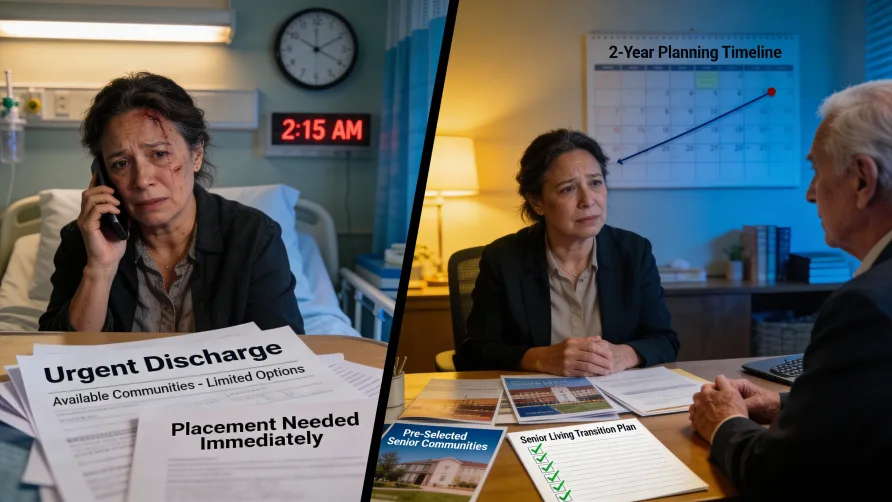

What Families Often Underestimate: Starting This Conversation Two Years Too Late

The ideal time to discuss senior living is while your parent is still healthy, active, and able to evaluate communities based on lifestyle preferences rather than urgent care needs. That conversation should happen around age 75 to 78 for most parents, even when everything seems fine.

Most families wait until age 82, after falls, after hospitalizations, after your parent can no longer manage independently. At that point, you're not choosing between communities. You're scrambling to find any community with immediate availability that can handle your parent's care needs.

Your mother could have toured ten communities, chosen the one she loved, moved in while physically able to participate in activities, and built friendships over years. Instead, she's moving during a crisis to whichever community has an opening, arriving when she's at her weakest and least able to adjust.

This timing difference matters enormously for both outcomes and the conversation itself. Talking to a healthy 76-year-old parent about "planning ahead" is infinitely easier than talking to a frail 83-year-old parent about "you can't stay here alone anymore."

Start earlier than feels necessary. You'll either have an easier conversation or you'll establish a framework that makes later conversations possible when circumstances change.

The Conversation Framework: What Actually Works

Forget the idea of one perfect conversation that solves everything. This isn't a single talk. It's an ongoing dialogue that happens over months or even years.

Phase 1: Plant the Seed (First Conversation)

Goal: Introduce the concept without pressure. Get your parent thinking about the future without demanding immediate decisions.

When: During a calm moment when your parent seems receptive, not during or immediately after a health crisis.

Approach: "Mom, I've been thinking about your future. Not because anything is wrong now, but because I want to make sure we're planning ahead. Have you ever thought about what you'd want to do if maintaining the house gets too hard?"

This is gentle exploration, not an intervention. You're asking about your parent's thoughts, not delivering verdicts about their capabilities.

Phase 2: Gather Information Together (Second Conversation)

Goal: Move from abstract discussion to concrete research without commitment.

When: A few weeks after the first conversation, once your parent has had time to think.

Approach: "Remember when we talked about future plans? I found some senior living communities nearby that look really nice. Would you be willing to just tour one with me? Not to move, just to see what's available these days. I'm curious what they're like now compared to what they used to be."

You're framing this as research and education, not as shopping for where your parent will live. The word "curious" signals low stakes. "Just to see" removes pressure.

Phase 3: Process and Discuss (Third Conversation)

Goal: Talk through what you learned and address concerns without pushing for decisions.

When: After touring one or two communities.

Approach: "What did you think about that place we toured? I was surprised by how nice it was. What stood out to you?"

Listen more than talk during this phase. Your parent's reactions and concerns tell you what matters to them and what objections you'll need to address later.

Phase 4: Connect Benefits to Current Struggles (Ongoing Conversations)

Goal: Help your parent see how senior living solves problems they're already experiencing.

When: As opportunities arise naturally in conversation.

Approach: When your mother mentions she's tired of cooking: "You know, that community we toured handles all the meals. You'd never have to cook again if you didn't want to."

When your father complains about yard work: "I remember that place had all the maintenance included. No more worrying about the lawn."

You're not pushing. You're connecting dots between their stated frustrations and solutions senior living provides.

Phase 5: Make the Plan (Final Decision)

Goal: Move from "someday" to "when."

When: When your parent shows openness or when circumstances require action.

Approach: "I think it might be time to seriously consider moving to senior living. I know it's a big decision. How do you feel about visiting those communities again and picking one?"

Real Conversation Starters That Work

Generic opening lines like "We need to talk" create immediate defensiveness. Specific, contextual conversation starters feel more natural and less threatening.

After a Hospitalization or Health Scare:

"Dad, this hospital stay scared me. I've been thinking about ways to make sure you have help available if something like this happens again. Have you thought about places where staff is available 24/7?"

This frames senior living as a safety solution, not a punishment for being sick.

When Your Parent Mentions Loneliness:

"I hate that you're alone so much since Mom died. I found some communities where there are activities and people around all the time. Would you want to look at them with me? You might actually enjoy having neighbors your age again."

You're offering a solution to a problem your parent has already identified, not creating a problem.

When Home Maintenance Becomes Overwhelming:

"I know you're frustrated with the house maintenance. What if we looked at places where that's all handled for you? You could actually enjoy retirement instead of spending every weekend on repairs."

This positions senior living as freedom from burden, not admission of failure.

When You Can't Provide All the Help Your Parent Needs:

"I want to help you more, but with work and my family, I can't be here as much as you need. I've been looking at communities where staff can help with things I can't. Can we look at options together?"

This acknowledges limitations honestly without blaming your parent for needing help.

When Your Parent Brings It Up First:

"I've been thinking I might not be able to stay here much longer."

Don't panic or disagree. Respond with: "I've had the same thought. Should we start looking at what's available? We don't have to decide anything immediately, but it would be good to know what options exist."

When your parent opens the door, walk through it. Don't wait for them to bring it up again. They might not.

Addressing Specific Objections: The Deep Dive

Your parent will have objections. These are predictable, emotionally charged, and need to be addressed with empathy rather than logic. Here's how to respond to the most common resistance points.

"I don't want to leave my home."

This is the deepest, most emotionally resonant objection. This house holds decades of memories. It's where they raised children, celebrated holidays, built a life. You're not just asking them to change addresses. You're asking them to leave their past.

What Doesn't Work:

"The house is too much for you now." This minimizes their attachment and focuses on limitations.

"You'll make new memories somewhere else." This dismisses the value of existing memories.

What Works:

"I understand completely. This house holds so many memories. I remember [specific memory]. Nobody is saying those memories don't matter or that you have to forget this place."

Acknowledge the loss first. Validate that this is hard and sad. Give them permission to grieve.

Then, gently: "The question is whether staying here is really letting you enjoy retirement. If you're spending all your time maintaining the house instead of doing things you enjoy, this house might be preventing the life you want to have now."

Reframe leaving as choosing a better quality of life, not abandoning the past.

Alternative Approach:

"What if we didn't think of it as leaving home permanently, but as trying something new? You could rent the house out for a year, try senior living, and if you hate it, you can move back."

This makes the decision less final and less frightening. Some parents need the safety net of knowing return is possible even if they rarely use it.

"I can't afford it."

Often this objection masks deeper fears. Sometimes your parent genuinely doesn't understand their finances. Other times they're worried about leaving nothing for children. Occasionally they're right and affordability is a real barrier.

What Doesn't Work:

"Yes, you can. I've looked at your finances." This feels invasive and dismissive of their concerns.

"We'll figure it out." This provides no real reassurance.

What Works:

"Can we sit down together and look at the actual costs? I'd like to understand your budget with you and see what's realistic."

If you're right that they can afford it, walking through actual numbers helps: "Your Social Security and pension are $4,000 monthly. Independent living costs $3,200. That leaves $800 for other expenses, plus you save on house costs like property tax, utilities, and maintenance. You might actually have more money available than you do now."

If finances are genuinely tight: "You're right that the nicest communities are expensive. But there are some more affordable options. Can we look at those and see if any work with your budget?"

Addressing the Inheritance Concern:

If your parent says "I want to leave you kids something," respond with: "Your quality of life right now is more important to us than inheritance later. We want you comfortable and happy. Please don't sacrifice that to save money for us."

"I'm not ready yet."

This is code for "I'm scared and I need more time."

What Doesn't Work:

"But you're 84 and living alone isn't safe." Pushing against "not ready" creates more resistance.

What Works:

"I hear that. What would make you feel ready? What needs to change?"

This opens dialogue about what "ready" means and what timeline your parent is imagining.

Then: "I'm not trying to rush you. I just want to make sure we're looking at options before a crisis forces us to decide quickly. Can we at least tour some places now so you know what's available when you are ready?"

This separates exploring options from committing to move, which reduces pressure.

Time-Based Approach:

"What if we picked a timeline? Like, we'll start seriously looking in six months. That gives you time to prepare, and it means we're not scrambling if something happens suddenly."

A timeline makes "not ready" feel less like indefinite avoidance and more like thoughtful planning.

"You're just trying to get rid of me."

This objection comes from deep fear of abandonment and loss of value in adult children's lives.

What Doesn't Work:

"That's ridiculous. Of course I'm not." Dismissing the fear doesn't address it.

What Works:

"I know this might feel that way, and I'm sorry if I made you feel that. That's not what's happening at all. I want to make sure you're safe and happy. Right now, I'm worried you're isolated and struggling with things that senior living could help with. This isn't about getting rid of you. It's about making sure you have the best life possible."

Name the fear, apologize for contributing to it, then explain your actual motivation.

Commitment Approach:

"If you move to senior living, I'll visit every [specific frequency]. I'll still call you every [specific frequency]. You're not losing me. I'm still your daughter and I'm still going to be part of your life. I just want you somewhere that provides help I can't provide while working full-time."

Specific commitments about ongoing contact reassure better than general promises.

"Senior living is for old people."

Your parent doesn't see themselves as "old" even if they're 85. Senior living feels like admitting they've crossed a threshold into elderly frailty.

What Doesn't Work:

"You are old, Dad. You're 85." Obviously true, but devastating to hear.

What Works:

"I think senior living is different than you're imagining. The people there are active and doing lots of things. It's not like a nursing home. Can we tour one so you can see what I mean? I think you'll be surprised."

Address the stereotyped image, don't address age.

Reframe Approach:

"You're right that you're not ready for a nursing home. That's not what we're talking about. We're talking about places designed for active people who just don't want to deal with house maintenance anymore. Lots of people move there in their 70s when they're still completely healthy."

Emphasize that this is about lifestyle choice, not medical necessity.

"I'll lose my independence."

For many seniors, independence is core identity. Senior living feels like becoming dependent, which feels like losing themselves.

What Doesn't Work:

"You're not independent now. You can't drive and I do all your shopping." Listing dependencies humiliates and doesn't address the emotional concern.

What Works:

"I think you'd actually have more independence in some ways. Right now you depend on me for rides and shopping. In senior living, transportation is provided and you wouldn't have to wait for me. You'd have your own apartment, your own schedule, and help available when you want it without having to ask family for everything."

Reframe independence as having access to resources without being dependent on specific people.

Choice Approach:

"You have more choices now than you will later. If we wait until something happens and you have to move quickly, you won't get to pick where you go. Choosing now while you're healthy means you stay in control."

Present the move as exercising independence and control rather than losing it.

"What about my stuff?"

Decades of accumulated belongings represent life history. The idea of sorting through and giving away those possessions feels overwhelming.

What Doesn't Work:

"You don't need all that stuff." Dismissing attachment to possessions dismisses their emotional significance.

What Works:

"You can take the things that matter most. Your apartment will have room for your favorite furniture, photos, and personal items. The things you love will come with you."

Then: "For the rest, we'll help you sort through it. We don't have to do it all at once. We can take it slowly."

Practical Approach:

Offer specific help: "I'll help you pack. We'll hire movers. You won't have to do this alone."

The fear isn't just about losing possessions. It's about the overwhelming work of dealing with them. Removing that barrier helps.

What Doesn't Work: Common Mistakes That Damage Relationships

Ambushing your parent with the conversation. "Everyone's here for an intervention about your living situation" creates defensiveness and feels like an attack.

Presenting it as a done deal. "We found you a place and you're moving next month" removes agency and control, which breeds resentment.

Making it about your convenience. "It's too hard for me to keep helping you" places burden on your parent for needing help rather than framing senior living as a positive solution.

Comparing your parent to others. "Mrs. Johnson moved to senior living and loves it" invites "I'm not Mrs. Johnson" and doesn't address your parent's specific situation.

Using scare tactics. "What if you fall and nobody finds you for days?" creates fear and anxiety rather than opening productive conversation.

Having this conversation alone if siblings exist. Other adult children should be involved in the discussion so your parent doesn't feel pressured by one child's opinion.

The Sibling Coordination You Need Before Talking to Parents

If you have siblings, align with them before approaching parents. The worst outcome is siblings disagreeing in front of your parent, which gives them ammunition to play children against each other.

Have a family meeting without your parents first. Discuss:

- Does everyone agree senior living is necessary?

- What's the timeline?

- What's the financial plan?

- Who will do the research on communities?

- How will you present a united front?

If siblings disagree fundamentally (one thinks Mom should move to senior living, another thinks she's fine at home), resolve that before involving your parent. Parents who sense division will exploit it, not maliciously, but because it supports their desire to avoid change.

Present the conversation to your parent together when possible. "We've all been talking and we're concerned about you living alone" carries more weight than one child raising concerns solo.

When Your Parent Says Yes: Moving From Agreement to Action

Sometimes, miraculously, your parent agrees. They say "You're right, it's probably time." Don't let relief make you complacent. Agreement today doesn't guarantee action tomorrow.

Immediate Next Steps:

Set a specific timeline: "Let's plan to tour communities in the next two weeks. Can we look at calendars and pick dates now?"

Vague "we should start looking" becomes "we'll do it eventually" which becomes never. Specific dates create accountability.

Research Together:

"Let's each look at a few communities online and compare notes. Then we'll narrow it down to the top three to tour."

Joint research keeps your parent involved and invested rather than having decisions made for them.

Tour Multiple Communities:

Visit at least three communities before making decisions. Seeing options helps your parent feel they're choosing rather than accepting the only possibility.

Make a Decision Relatively Quickly:

Once you've toured communities, don't let the decision drag out for months. Your parent's initial enthusiasm will wane. Strike while openness exists.

"Which community did you like best? Should we go back for a second visit there and talk seriously about moving?"

When Your Parent Says No: Knowing When to Push and When to Wait

Not every "no" means the conversation is over. Not every "no" should be pushed against.

Wait If:

- Your parent is still safe living independently

- No immediate health or safety concerns exist

- They're genuinely not ready and have a reasonable timeline in mind

- Pushing now would permanently damage your relationship

Push Through Resistance If:

- Safety concerns are immediate and serious

- Your parent's health is declining rapidly

- Current living situation is unsustainable for caregivers

- Waiting increases risk significantly

When you need to push despite resistance, be direct: "I know you don't want to do this. I understand you're angry with me. But staying here alone isn't safe anymore. We need to make a change even though you disagree. I'm sorry this feels forced, but your safety is more important than waiting for you to be ready."

This is hard. Your parent may not forgive you quickly. But sometimes the most loving choice feels the least loving in the moment.

The Real Timeline: What to Expect

Months 1-2: Initial conversations. Planting seeds. Lots of "not ready yet" and "I'll think about it."

Months 3-4: Tours begin. Your parent starts seeing actual communities rather than imagining them abstractly. Objections become more specific and concrete.

Months 5-6: Processing. Your parent might seem to withdraw from the conversation. They're adjusting to the idea internally even if they're not ready to commit externally.

Month 6-8: Decision. Either circumstances create urgency or your parent reaches acceptance. Move-in planning begins.

Month 8-10: The actual move happens.

This timeline assumes relatively cooperative parents without crisis forcing faster action. Some parents move faster. Many take longer. The key is not rushing the process unless safety requires it.

After the Move: Your Role Doesn't End

Your parent moves to senior living. Your job isn't done. The first few weeks are critical for adjustment.

Visit frequently initially. Multiple times per week if possible. Your presence reassures them during difficult transition.

Help them get involved in activities. Walk them to the first few events. Introduce them to other residents. Facilitate social connection.

Listen to complaints without immediately solving them. "The food isn't as good as home cooking" doesn't need "Well, you can't cook anymore so this is what we have." It needs "I know it's an adjustment. What did they serve today?"

Give adjustment time. Three months minimum before judging whether the move was successful. Initial resistance doesn't mean permanent unhappiness.

The Bottom Line

Talking to parents about senior living is hard because you're asking them to acknowledge aging, accept help, and leave familiar surroundings. There's no magic script that makes this easy.

What works is starting earlier than feels necessary, having multiple small conversations instead of one big one, focusing on benefits rather than limitations, addressing objections with empathy rather than logic, and accepting that your parent needs time to adjust to ideas that feel threatening.

The families who handle this well are those who start the conversation before crisis forces it, present options rather than ultimatums, involve parents in decisions rather than making decisions for them, and maintain close connection after the move.

Your relationship with your parent matters more than the perfect conversation. Approach this with love, patience, and recognition that what you're asking is genuinely difficult for them. The goal isn't winning an argument. It's ensuring your parent's safety and quality of life while preserving the relationship you value.

Start the conversation. Give it time. Stay involved. Trust that you're doing the right thing even when it feels hard. Your parent may not thank you now, but ensuring they're safe and cared for is how love looks when difficult decisions become necessary.