The label "memory care" doesn't guarantee dementia expertise.

You can tour a facility with locked doors and memory boxes outside each room, hear about their "specialized programming," and still have no clear picture of whether the staff actually knows how to care for someone with dementia. Here's what most families don't realize until after they've signed the contract: in most states, a community can call itself "memory care" without meeting any dementia-specific training requirements. The housekeeping staff might have the same dementia education as the direct care workers. The activities director might have learned everything they know from a three-hour online course.

This matters because dementia isn't just memory loss. It changes how your parent perceives depth, processes sound, interprets facial expressions, and experiences time. It creates behaviors that look irrational but follow their own internal logic. And caring for someone through these changes requires specific knowledge that general senior care training simply doesn't cover.

Some memory care facilities have staff trained in evidence-based dementia protocols. They understand why your mother keeps trying to "go home" even though she's lived there for six months. They know how to respond when your father becomes convinced the staff is stealing from him. They've learned techniques for helping someone bathe who has become terrified of water. Other facilities just lock the doors and hope for the best.

This article will show you what genuinely specialized memory care for dementia actually looks like, what training and protocols should be in place, and how to tell the difference between facilities that truly understand dementia and those that simply house people who have it.

What Makes Dementia Care Actually Specialized

Specialized dementia care isn't defined by locked doors or memory-themed decor. It's built on three foundations: staff who receive comprehensive, ongoing training in dementia-specific protocols, environments designed around how dementia changes perception and behavior, and structured approaches that address the neurological reality of the disease rather than treating symptoms as behavioral problems to be managed.

When these elements are present, you see different outcomes. Residents experience less distress. Families report better communication. Staff turnover drops. These differences are measurable and they're directly connected to whether the care approach is genuinely specialized for dementia.

Specialized Dementia Training and Protocols

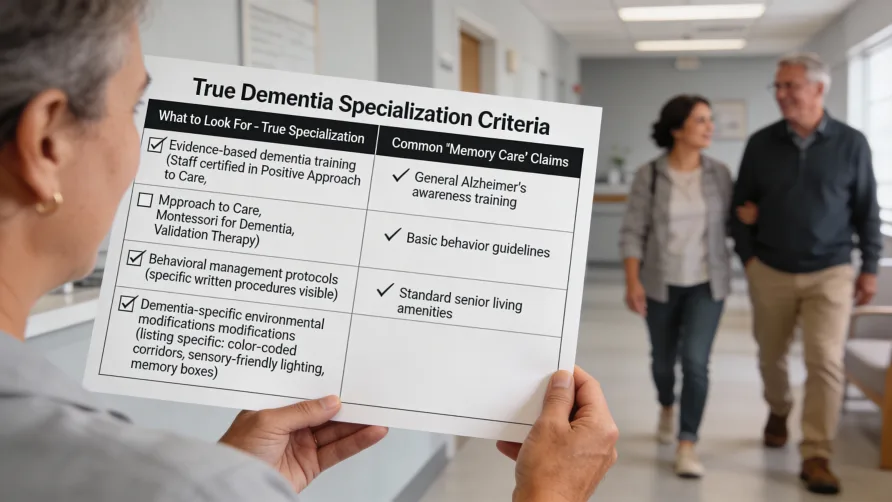

Here's where the gap between "memory care" and specialized dementia care becomes clearest.

Federal regulations require nursing facilities to provide some dementia management training, but the requirements are minimal. Under 42 CFR 483.95, nurse aides must receive at least 12 hours of annual in-service training that includes dementia management, but there's no specification about what that training must cover or how deep it must go. In many facilities, this means watching a video about validation therapy once a year.

State requirements vary dramatically. As of 2025, states like Minnesota require direct care staff in memory care facilities to complete eight hours of initial dementia training within 80 working hours of hire, plus two hours annually. Oregon mandates six hours of annual dementia training covering specific topics including disease progression, managing symptoms without antipsychotic medications, and addressing social needs. Colorado's Senate Bill 22-079, implemented in January 2024, established enhanced training standards after data showed 42% of assisted living residents had dementia but staff often lacked specialized preparation.

Arizona requires between 20 and 69 hours of dementia training depending on the care level provided, with House Bill 2764 establishing licensure subclasses specifically for memory care facilities. Florida requires completion of state-approved ADRD training within 30 days of hire for anyone providing personal care to people with dementia. California implemented the first major update to dementia care regulations in decades, effective January 2025, with comprehensive new requirements around training, assessment, and care planning.

But training hours alone don't tell you what staff are actually learning.

Specialized dementia training covers specific protocols most general care training never touches. Staff learn the neurological basis of dementia behavior, how different types of dementia progress, and why standard caregiving approaches often backfire with dementia patients. They're trained in person-centered communication techniques, particularly validation therapy, which research shows significantly improves cooperation and reduces distress.

Validation therapy, developed by Naomi Feil and refined over decades, teaches staff to enter the emotional reality of the person with dementia rather than trying to correct or reorient them. When your father insists he needs to pick up his children from school (children who are now 50 years old), validation-trained staff understand this expresses an unmet need, probably anxiety about responsibilities or connection to family. They know how to acknowledge the feeling without reinforcing the confusion: "You're thinking about your kids. You always took care of them. That was important work."

Research from the University of Kansas Medical Center found that when caregivers used validation techniques like affirmations and verbalizing understanding, people with dementia showed an 11% probability of cooperative response versus negative reactions to non-validating communication. This matters in practical terms. It's the difference between a bath that traumatizes everyone involved and one that happens calmly because the staff member recognized the fear and addressed it before trying to help with washing.

Person-centered care protocols, supported by extensive research, teach staff to view behaviors as communication. When someone with dementia becomes agitated before dinner, specialized training helps staff recognize this might be sundowning (increased confusion in late afternoon), overstimulation from a noisy dining room, or unmet physical needs like pain or thirst. They know to reduce stimulation, check for discomfort, and adjust the routine rather than viewing the agitation as a problem to suppress.

In practice, this is where things break down. Many facilities say they use person-centered care or validation therapy, but their staff have only received surface-level training. They know the vocabulary without understanding the approach. You'll hear them telling residents "you're safe here" while physically blocking them from walking, or redirecting concerns without ever acknowledging the underlying emotion. They're following scripts rather than applying trained judgment to individual situations.

Specialized facilities invest in ongoing education. The Alzheimer's Association recognizes training programs that cover five core topic areas including understanding dementia progression, communication strategies, person-centered care approaches, managing responsive behaviors, and creating supportive environments. Programs range from three hours to 20 hours, but completion is just the starting point. Facilities with genuine dementia expertise require annual continuing education, regular competency assessments, and case reviews where staff discuss challenging situations and refine their approaches.

They also train everyone, not just direct care staff. In truly specialized programs, housekeepers learn why a resident might become distressed by vacuuming sounds and how to adapt their schedules. Kitchen staff understand why plate presentation matters for someone who can't distinguish white food on white plates. Maintenance workers know which repairs can wait and which represent safety concerns specific to dementia.

The cultural difference is profound. In general memory care, staff manage dementia as a complication. In specialized care, staff understand dementia as the central reality that shapes every interaction, every environmental choice, every moment of the day.

Dementia-Specific Environment Design

The physical environment either supports people with dementia or creates additional disability.

Specialized memory care facilities incorporate design elements based on how dementia changes sensory processing and spatial navigation. Flooring uses solid colors without patterns because people with dementia often perceive dark borders or contrasting tiles as holes or steps, causing them to avoid walking through spaces or shuffle along walls. This same principle works in reverse. Facilities place black mats or high-contrast flooring in front of exits they want residents to avoid, as the visual creates a natural barrier.

Lighting operates on multiple levels. Natural light exposure helps regulate circadian rhythms, reducing sundowning and sleep disturbances. Many newer facilities install LED systems with controllers that adjust both intensity and color temperature throughout the day, raising light levels during activities to increase attention and lowering them before rest periods to promote calm. Glare and shadows are minimized because they create visual confusion and can be perceived as obstacles or threats.

Color and contrast guide navigation and support remaining function. Toilet seats in a contrasting color to the floor help residents locate bathrooms independently. Handrails in colors that stand out from walls provide clear visual cues. Dining plates use contrasting colors to help residents distinguish food items. Door frames, light switches, and furniture legs all use color differentiation to support visual processing that's been compromised by dementia.

Wayfinding goes beyond directional signs. Specialized facilities use memory boxes with personal items, large photographs, and distinctive artwork to help residents recognize their rooms. Common areas feature clear sight lines to key destinations like dining rooms and bathrooms. Circular walking paths allow safe wandering without dead ends that cause frustration. Landmarks like distinctive furniture or aquariums provide reference points.

Security features blend into the environment rather than announcing themselves. Exit doors might be disguised with murals or wallpaper that makes them visually recede. Keypad locks use trick buttons that require specific sequences staff know but residents can't replicate. Garden fences reach at least six feet but are designed to look like natural boundaries. Some facilities use wearable tracking devices and passive monitoring systems rather than obvious locks and alarms.

Outdoor spaces matter enormously. Secure gardens with circular paths, raised planting beds residents can tend, and varied textures and scents provide sensory stimulation and physical activity opportunities. Research consistently shows access to nature reduces agitation and improves sleep and appetite. The challenge is making outdoor areas genuinely accessible and appealing rather than just meeting licensing requirements for "secure outdoor space."

Noise control receives serious attention in specialized environments. Hard surfaces and high ceilings create echoes that disorient people with dementia and increase agitation. Specialized facilities use acoustic treatments, sound-absorbing materials, carpeting, and separated spaces for quiet and active areas. They avoid overhead paging systems and minimize background noise from televisions and radios.

The overall design reduces choices and simplifies the environment. Kitchenettes are removed from residential units because of safety concerns. Closets contain limited clothing options to reduce decision-making stress. Clutter is eliminated because it creates visual confusion. This isn't about infantilizing residents. It's about removing environmental barriers that dementia has created.

Behavioral Management Approaches in Specialized Care

Specialized dementia care views behaviors as symptoms with underlying causes rather than problems to control.

When someone with dementia repeatedly asks to go home, attempts to leave the building, or becomes aggressive during personal care, specialized staff follow structured assessment protocols. They consider time of day (sundowning), recent changes in routine or environment, unmet physical needs including pain, medication side effects, overstimulation or understimulation, and whether the behavior communicates something specific.

The first response is never pharmaceutical. Research on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) consistently shows nonpharmacological interventions should be first-line approaches. Specialized facilities implement sensory practices like aromatherapy, massage, and music therapy. They use psychosocial approaches including reminiscence therapy, meaningful activities matched to remaining abilities, and structured protocols for challenging care tasks like bathing and mouth care.

Bathing protocols in particular distinguish specialized care. Staff are trained in specific techniques for someone who has become fearful of bathing: warming the bathroom first, explaining each step out loud, using towels for modesty throughout, matching water temperature preferences, never forcing someone into a shower, and sometimes accepting a bed bath as success. They understand resistance isn't stubbornness. It's often terror of falling, confusion about what's happening, or sensitivity to water temperature.

Pain assessment happens regularly even when residents can't verbally report discomfort. Specialized staff learn to recognize nonverbal indicators like facial expressions, body language, changes in behavior patterns, and resistance to movement. They know that aggression during dressing might indicate arthritis pain, not combativeness.

Activities are structured around stimulating cognition while respecting current abilities. Music therapy uses familiar songs from residents' young adulthood to access long-term memories and improve mood. Reminiscence therapy with photographs and objects from the past provides opportunities for meaningful conversation and connection. Montessori-based activities break complex tasks into manageable steps that allow residents to experience success and maintain dignity.

The care approach adjusts as dementia progresses. Early-stage residents might participate in cognitively demanding activities and maintain semi-independent routines. Middle-stage care focuses on structured schedules, simplified choices, and activities that engage without overwhelming. Late-stage care emphasizes comfort, sensory stimulation, and maintaining connection through touch and music even when verbal communication is no longer possible.

How This Differs from General Care

General assisted living or basic memory care provides supervision and help with daily activities. Staff ensure residents are safe, fed, bathed, and have their medications. This meets the definition of custodial care.

Specialized dementia care builds on that foundation with protocols designed around the neurological reality of dementia. Staff don't just supervise. They understand that the person who keeps removing their clothes isn't being inappropriate, they're uncomfortable and can't communicate it verbally. They know the resident who becomes agitated every afternoon isn't just difficult, they're experiencing sundowning and need reduced stimulation and a predictable routine.

The difference shows up in crisis situations. When a resident becomes distressed and attempts to leave, general care staff might physically redirect or use pharmaceutical intervention. Specialized staff assess what triggered the behavior, validate the underlying emotion, address any physical needs, and use environmental modifications and communication techniques to reduce distress without restraint or medication.

Staff-to-resident ratios are typically higher in specialized care, with some facilities maintaining one staff member per five residents in memory care versus higher ratios in general assisted living. This allows time for the slower pace and individual attention dementia care requires. It also means staff can implement person-centered protocols rather than just completing tasks.

The daily structure reflects dementia-specific needs. Meal times accommodate the slower eating pace and need for assistance. Activities are designed to engage without overwhelming. Quiet spaces are available for residents who become overstimulated. Routines remain consistent because unpredictability increases confusion and distress.

Warning Signs Your "Memory Care" Facility Lacks True Dementia Expertise

Watch for these red flags during tours and conversations.

Staff can't explain their dementia training beyond "we've all been trained." Ask specific questions about hours of training, who provides it, whether it covers validation therapy or person-centered care approaches, and how often continuing education happens. Vague answers indicate minimal preparation.

The environment shows no evidence of dementia-specific design. Standard assisted living with locked doors isn't specialized memory care. Look for intentional color contrasts, modified lighting, circular walking paths, disguised exits, and memory boxes or personalized markers for rooms.

Staff talk about residents using facility-centered language. Phrases like "she's a wanderer" or "he's a difficult patient" suggest they view behaviors as problems rather than communication. Listen for whether they describe understanding what triggers certain behaviors and how they respond.

Activities are generic. Bingo and movie watching aren't dementia-specialized programming. Ask about person-centered activities, music therapy, reminiscence work, and how they adapt activities for different stages of dementia progression.

They claim all memory care is basically the same. This either indicates ignorance about specialized protocols or intentional misrepresentation. Press for specifics about what makes their care specialized.

High staff turnover suggests problems with training, support, or organizational culture. Ask about their turnover rate and average tenure of direct care staff. Experienced staff who stay build relationships with residents and develop expertise that temporary workers can't match.

Questions That Reveal Real Dementia Specialization

Ask these questions on tours and during evaluation calls.

What specific dementia training do direct care staff complete? How many hours? What topics are covered? Who provides the training and what are their credentials? How often is continuing education required?

How do you handle situations when a resident becomes distressed or tries to leave? Listen for whether they describe assessment protocols, validation techniques, and individualized responses versus generic redirection or security measures.

What's your approach to someone who resists bathing or becomes aggressive during personal care? Specialized facilities describe specific protocols and staff training for these common situations.

How do you manage behavioral symptoms without medication? Ask about their nonpharmacological interventions and when they consider psychiatric medication appropriate.

What's your staff-to-resident ratio during the day and at night? How many residents does each caregiver typically work with during a shift?

Can you show me your specialized environmental features? Ask them to walk you through design elements specific to dementia rather than general accessibility features.

How do you train staff who aren't direct caregivers, like housekeeping and kitchen staff? In specialized facilities, everyone receives dementia education.

What's your staff turnover rate? What's the average length of time direct care workers stay employed here?

How do you involve families in care planning? What information do you need from families about the person's history, preferences, and routines?

What happens when dementia progresses? Do you provide care through all stages or is there a point where residents need to move to a different level of care?

The Bottom Line on Specialized Dementia Care

Memory care for dementia should mean your parent receives care from staff who understand the disease, in an environment designed for how dementia changes perception and behavior, with protocols that address underlying needs rather than suppressing symptoms.

This level of specialization exists, but it's not guaranteed by the "memory care" label. State regulations vary dramatically. Even in states with strong requirements, enforcement is inconsistent. Many facilities operate in the gray area between meeting minimum standards and providing genuinely specialized care.

The responsibility falls on families to evaluate whether a facility's dementia care is actually specialized. This means asking specific questions, observing how staff interact with residents, examining the physical environment for dementia-specific design, and checking state licensing records for training requirements and compliance history.

When you find specialized dementia care, the difference is profound. Your parent experiences less distress. Behavioral symptoms reduce because underlying needs are being addressed. They maintain more function longer because the environment supports rather than disables them. You feel confident that difficult situations will be handled with expertise rather than just managed with medication and locked doors.

This is what memory care for dementia should be. Make sure it's what you're actually getting.